Spatial and Temporal analysis of Electoral violence of the Nigerian Elections 2003

Published:

Nigeria in 2003 held more than one election in the same month.It started with the House of the representative and Senate elections on the same day, 12th of April 2003. Then the presidential election was held on 19th of April 2003. Then on the 3rd of May 2003, the National Assembly election was conducted. According to the data collected by HRW, violence started earlier in Delta state from January to March as it is the most oil-producing state in Nigeria. The violent incidents included clashes between different ethnic groups and other clashes between armed groups and security forces. The most violent incidents were on 12th and 19th of April and the 3rd of May (on election days(s) violence). In most of the incidents the ruling party was the main perpetrator. Some incidents started earlier on 10th and 11th and some took place during the first three days of May. The violence started on 10th of April in Bassambiri area in Bayelsa state in the form of clashing thugs belong to opponent parties. On the 11th different violent incidents took place in different areas (Amadi-amain in River state and Warri in Delta state) in the form of the temporary displacement of people from their homes and attacks waged by the opponent’s party’s supporters.

On 12th of April (the House of the representative and Senate election day) violence broke out in different states and different areas within the same state. Violent incidents were recorded in Bayelsa state, different regions in River state (Amadi-ama, Etche, Ikwerreland and Ogoniland) and in Warri and Ughelli regions in Delta state. The violence took the form of of violent protests, killings of opponent’s parties’ supporters, kidnapping and prevention of election observers from obtaining election results. Violence continued on the 13th of April in Ogoniland in River state by security forces.

The second wave of violence was on the 19th of April (the presidential election day). The incidents took place in Oporoma region in Bayelsa State and in Ogbio-Akpor, Ikwerreland and Port Harcourt regions in River state. The violent incidents were clashes over voting materials, killings in clashes between rival parties’ supporters and repression by security forces in front of peaceful demonstrations.

Violence continued in some states till May. On 3rd of May (the National Assembly election) violent incidents increased again in River state and Delta state. Most if the incidents were clashes and confrontations between armed groups and violence held by security forces (HRW, 2004).

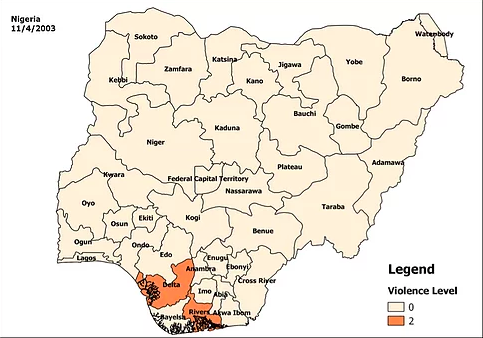

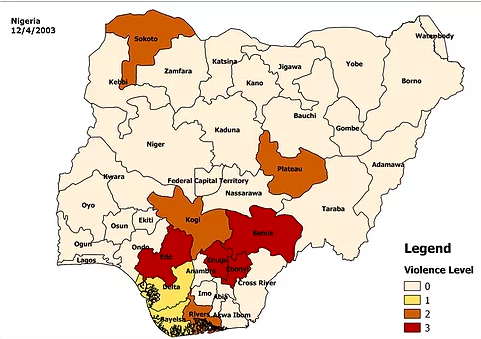

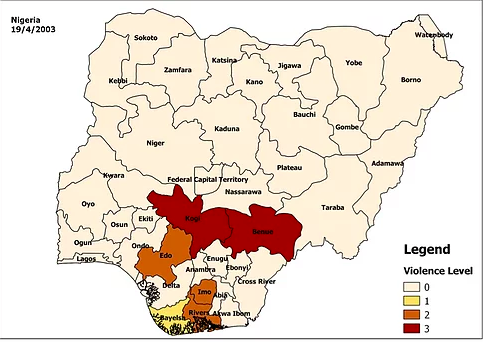

Figure 2.1 to 2.6 show maps of the spatial and temporal diffusion of electoral violence in Nigeria. The maps are cartographied (coloured) based on the level of violence the “0” class reflects no violence, the “1” class means low level of violence like intimidation or harassment, the “2” class means high violent level like assassinations or targeted murder and the “3” class refers to extensive violence like generalized physical attacks and killings. The incidents reported in the HRW report were coded using Stratus and Taylor coding (Straus & Taylor, 2009).

The maps show that violence is concentrated in four main areas Niger Delta states (Delta, Rivers, Imo, Edo and Bayelsa), Middle Belt states (Plateau and Benue), South Central states (Ebonyi, Kogi and Enugu) and South West states (Lagos) and North West states (Sokoto). Although the Niger Delta states are rich in natural resources like oil, they are vulnerable to violence because of the uneven distribution of resources from the oil industry, informal networks of patronage, minorities tension and social fragmentation. Different causes can be found in the Middle states which are terrorism, economic conditions, ethnic and religious polarization. In the South West states there are different armed groups like Eiye, Aiye, Lord, Black Axe, and KK confraternities and the cults conflicts. The drivers of violence in the South Central states are corrupt, ethnicity, unemployment, illiteracy and the existence of gangs. The North West states were calmer compared to the rest of the areas. These states are so diverse socio-economically, they comprise some of the richest and poorest states in Nigeria. This diversity could be the reason behind the rare occurrence of violence (Falola, 1998).

We also can infer from the data and the maps that electoral violence takes the form of parallel incidents in different areas on the election day(s). This pattern may take different forms in different countries. This detailed level of information about locations and times of the violent incidents helps in the prediction and the generation of a statistical assessment tool for violence. Such a tool can predict if violence will take place and when and where it will reach its peak.

Figure 2.1: diffusion of electoral violence in Nigeria on 11/4/2003

Figure 2.2: diffusion of electoral violence in Nigeria on 12/4/2003

Figure 2.3: diffusion of electoral violence in Nigeria on 13/4/2003

Figure 2.4: diffusion of electoral violence in Nigeria on 19/4/2003

Figure 2.5: diffusion of electoral violence in Nigeria on 23/4/2003

Figure 2.6: diffusion of electoral violence in Nigeria on 3/5/2003

References

(UNDP), U. N. D. P. (2009). Elections and Conflict Prevention Guide. In U. N. D. P. U. (2009) (Ed.), Electoral Systems and Processes (pp. 58). UNDP: UNDP.

Adolfo, E. V., Söderberg Kovacs, M., Nyström, D., & Utas, M. (2012). Electoral Violence in Africa.

Aggarwal, L. K., & Evan, W. M. (1985). POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND INCOME INEQUALITY. Peace Research, 17(3), 46-50. doi: 10.2307/23610093

Alesina, A., Özler, S., Roubini, N., & Swagel, P. (1996). Political instability and economic growth. Journal of Economic Growth, 1(2), 189-211. doi: 10.1007/BF00138862

Anderson, D., & Lochery, E. (2008). Violence and exodus in Kenya’s Rift Valley, 2008: Predictable and preventable? Journal of Eastern African Studies, 2(2), 328-343.

Aver, T. T., Nnorom, K. C., & Targba, A. (2013). Political Violence and its Effects on Social Development in Nigeria. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 3(17), 261-266.

Bekoe, D. A. O. (2012). Voting in fear: electoral violence in Sub-Saharan Africa: United States Institute of Peace.

Berenschot, W. (2011). The spatial distribution of riots: Patronage and the instigation of communal violence in Gujarat, India. World Development, 39(2), 221-230.

Bhasin, T., & Gandhi, J. (2013). Timing and targeting of state repression in authoritarian elections. Electoral Studies, 32(4), 620-631.

Birch, S. (2011). Electoral malpractice: Oxford University Press.

Boone, C. (2011). Politically allocated land rights and the geography of electoral violence: The case of Kenya in the 1990s. Comparative Political Studies, 0010414011407465.

Boone, C., & Kriger, N. (2012). Land patronage and elections: winners and losers in Zimbabwe and Côte d’Ivoire: USIP Press.

Braun, R. (2011). The diffusion of racist violence in the Netherlands: Discourse and distance. Journal of Peace Research, 48(6), 753-766.

Brown, S., & Sriram, C. L. (2012). The big fish won’t fry themselves: Criminal accountability for post-election violence in Kenya. African Affairs, ads018.

Collier, P. (2011). Wars, guns and votes: Democracy in dangerous places: Random House.

Collier, P., & Vicente, P. C. (2012). Violence, bribery, and fraud: the political economy of elections in Sub-Saharan Africa. Public Choice, 153(1-2), 117-147.

Crost, B., Felter, J., Mansour, H., & Rees, D. I. (2013). Election Fraud and Post-Election Conflict: Evidence from the Philippines.

Daley, P. (2006). Ethnicity and political violence in Africa: The challenge to the Burundi state. Political Geography, 25(6), 657-679. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2006.05.007

Daxecker, U. E. (2012). The cost of exposing cheating International election monitoring, fraud, and post-election violence in Africa. Journal of Peace Research, 49(4), 503-516.

Daxecker, U. E. (2014). All quiet on election day? International election observation and incentives for pre-election violence in african elections. Electoral Studies, 34, 232-243.

De Juan, A. (2012). Mapping political violence: The approaches and conceptual challenges of subnational geospatial analyses of intrastate conflict: GIGA Working Papers.

Dercon, S., & Gutiérrez-Romero, R. (2012). Triggers and characteristics of the 2007 Kenyan electoral violence. World Development, 40(4), 731-744.

Donno, D. (2013). Defending democratic norms: international actors and the politics of electoral misconduct: Oxford University Press.

EISA. (2010). preventing and managing

violent election-related

conflictS in Africa (pp. 39): Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa.

Falola, T. (1998). Violence in Nigeria: The crisis of religious politics and secular ideologies: University Rochester Press.

FEARON, J. D., & LAITIN, D. D. (2003). Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War. American Political Science Review, 97(01), 75-90. doi: doi:10.1017/S0003055403000534

Fischer, J. (2002). Electoral Conflict And Violence (A strategy for study and prevention). .

Fjelde, H., & Höglund, K. (2014). Electoral Institutions and Electoral Violence in Sub-Saharan Africa. British Journal of Political Science, 1-24.

Flores, T. E., & Nooruddin, I. (2012). The effect of elections on postconflict peace and reconstruction. The Journal of politics, 74(02), 558-570.

Hafner-Burton, E. M., Hyde, S. D., & Jablonski, R. S. (2014). When do governments resort to election violence? British Journal of Political Science, 44(01), 149-179.

Hibbs, D. A. (1973). Mass political violence: A cross-national causal analysis (Vol. 253): Wiley New York.

Höglund, K. (2009). Electoral violence in conflict-ridden societies: concepts, causes, and consequences. Terrorism and Political Violence, 21(3), 412-427.

HRW, H. R. W. (2004). Nigeria’s 2003 Elections: The Unacknowledged Violence (pp. 47): Human Rights Watch.

Hyde, S. D., & Marinov, N. (2011). Which elections can be lost? Political Analysis, mpr040.

Kagwanja, P. (2009). Courting genocide: Populism, ethno-nationalism and the informalisation of violence in Kenya’s 2008 post-election crisis. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 27(3), 365-387.

Kasara, K. (2011). Electoral geography and conflict: Examining the redistricting through violence in Kenya: Mimeo: Columbia University.

Kelley, J. G. (2012). Monitoring democracy: When international election observation works, and why it often fails: Princeton University Press.

Kitschelt, H., & Wilkinson, S. I. (2007). Citizen-politician linkages: an introduction. Patrons, clients, and policies: Patterns of democratic accountability and political competition, 1-49.

Laakso, L. (2007). Insights into electoral violence in Africa. Votes, Money and Violence: Political Parties and Sub-Saharan Africa, 224-252.

Mares, I., & Petrova, T. (2013). Disaggregating Clientelism: Examining the Mix of Vote-Buying, Patronage and Intimidation. Columbia University. Typescript.

Mueller, S. D. (2008). The political economy of Kenya’s crisis. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 2(2), 185-210.

Muller, E. N., & Seligson, M. A. (1987). Inequality and Insurgency. American Political Science Review, 81(02), 425-451. doi: doi:10.2307/1961960

Neil, P. (2004). Essentials of comparative politics. NewYork, NY: WW Norton&Co.

Neumayer, E. (2004). The impact of political violence on tourism dynamic cross-national estimation. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 48(2), 259-281.

Onapajo, H. (2014). Violence and Votes in Nigeria: The Dominance of Incumbents in the Use of Violence to Rig Elections. Africa Spectrum, 49(2), 27-51.

Reilly, B. (2001). Democracy in divided societies: Electoral engineering for conflict management: Cambridge University Press.

Reilly, B. (2002). Elections in post-conflict scenarios: Constraints and dangers. International Peacekeeping, 9(2), 118-139.

Salehyan, I., Hendrix, C. S., Hamner, J., Case, C., Linebarger, C., Stull, E., & Williams, J. (2012). Social conflict in Africa: A new database. International Interactions, 38(4), 503-511.

Sberna, S., & Olivieri, E. (2014). ‘Set the Night on Fire!’Mafia Violence and Elections in Italy. Mafia Violence and Elections in Italy.

Schedler, A. (2013). The politics of uncertainty: Sustaining and subverting electoral authoritarianism: Oxford University Press.

Schutte, S., & Weidmann, N. B. (2011). Diffusion patterns of violence in civil wars. Political Geography, 30(3), 143-152. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.03.005

Sidel, J. T. (1997). Philippine politics in town, district, and province: Bossism in Cavite and Cebu. The Journal of Asian Studies, 56(04), 947-966.

Sigelman, L., & Simpson, M. (1977). A Cross-National Test of the Linkage between Economic Inequality and Political Violence. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 21(1), 105-128. doi: 10.2307/173685

Simpser, A. (2013). Why governments and parties manipulate elections: theory, practice, and implications: Cambridge University Press.

Sisk, T. D. (2012). Evaluating Election-Related Violence in Africa: Nigeria and Sudan in Comparative Perspective Voting in Fear: Electoral Violence in Sub-Saharan Africa: Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace.

Smith, L. (2012). Disturbance or Massacre? Consequences of Electoral Violence in Ethiopia. Voting in Fear, 181-208.

Staniland, P. (2013). Armed Groups and Militarized Elections.

Staniland, P. (2014). Violence and Democracy. Comparative Politics, 47(1), 99-118.

Straus, S., & Taylor, C. (2009). Democratization and Electoral Violence in Sub-Saharan Africa, 1990-2007. Paper presented at the APSA 2009 Toronto Meeting Paper.

Thorp, R., Caumartin, C., & Gray-Molina, G. (2006). Inequality, Ethnicity, Political Mobilisation and Political Violence in Latin America: The Cases of Bolivia, Guatemala and Peru*. Bulletin of Latin American Research, 25(4), 453-480. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-9856.2006.00207.x

Trelles, A., & Carreras, M. (2012). Bullets and votes: Violence and electoral participation in Mexico. Journal of Politics in Latin America, 4(2), 89-123.

UNOSAT (Cartographer). (2008a). Active Fire Locations in Rift Valley Province Following Kenyan National Elections [Satellite ]. Retrieved from http://www.unitar.org/unosat/node/44/1035

UNOSAT (Cartographer). (2008b). Chronology of Fire Locations in Rift Valley Province Following Kenyan National Elections [Satellite ]. Retrieved from http://www.unitar.org/unosat/node/44/1036

USAID. (2010). Electoral escurity framework (Technical guidance handbook for democracy and governance officers) (pp. 59). USAID: USAID.

Varshney, A. (2001). Ethnic Conflict and Civil Society: India and Beyond. World Politics, 53(03), 362-398. doi: doi:10.1353/wp.2001.0012

Vivanco, E., Olarte, J., Díaz-Cayeros, A., & Magaloni, B. (2014). Drugs, Bullets, and Ballots: The Impact of Violence on the 2012 Presidential Election Mexico’s Evolving Democracy

A Comparative Study of the 2012 Elections. The Johns Hopkins University Press CY: Baltimore SN.

von Borzyskowski, I. (2013). Sore Losers? International Condemnation and Domestic Incentives for Post-Election Violence.

Weede, E., & Muller, E. N. (1990). Cross-national variation in political violence. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 34, 624-651.

Weidmann, N. B., & Callen, M. (2013). Violence and election fraud: Evidence from Afghanistan. British Journal of Political Science, 43(01), 53-75.

Wilkinson, S. I. (2004). Votes and violence: Cambridge University Press Cambridge.

Zhukov, Y. M. (2012). Roads and the diffusion of insurgent violence: The logistics of conflict in Russia’s North Caucasus. Political Geography, 31(3), 144-156. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.12.002

Zwi, A., & Ugalde, A. (1989). Towards an epidemiology of political violence in the third world. Social Science & Medicine, 28(7), 633-642.